SPECTROstar Nano

Absorbance plate reader with cuvette port

Binding assays are used extensively for fundamental and applied biological research including many applications in drug discovery, pharmacology and medicinal chemistry. Learn about the most widely used binding assays and the different detection options available on microplate readers.

Dr Barry Whyte

Dr Barry Whyte

Binding assays can be performed in a wide variety of ways for different applications in the life sciences. They play a significant role in drug discovery and development and are frequently performed in many research settings in a wide variety of laboratories. The multitude of binding assays can be categorized according to the light detection technology being used and many of these assays are ideally suited to measurements on a microplate reader. This blog provides an overview of widely used binding assays and the different detection options available on microplate readers.

Ligand-binding assays are used to measure the interaction between a ligand and its target. These assays are essential for understanding how drugs interact with biological systems, assessing drug efficacy and safety and provide crucial insights into drug discovery and development.

Affinity binding assays are typically used to determine the strength of binding of a ligand (protein, peptide, or small molecule drug) to a target biomolecule. Therefore, many experiments require determination of the binding affinity of potential binding partners represented by the equilibrium dissociation constant KD, the concentration of ligand at which half the binding sites on a biomolecule are occupied at equilibrium. The target biomolecule could be another protein, antibody, DNA, RNA, G-protein coupled receptor, kinase, or one of many other receptors, which when activated by a ligand, produce a pharmacological effect in the body.

Once an affinity binding assay has been established for a ligand/biomolecule pair, competitive binding assays can be developed. Competitive binding assays involve experiments that evaluate the interaction of multiple ligands with a protein or other molecule by measuring the displacement of a labeled ligand from its binding site. They are often used to evaluate the affinity of new compounds in relation to known ligands.

Competitive binding assays allow for high-throughput screening of combinatorial or natural compound libraries. They can be used to develop drugs that can interfere with downstream events effected by activation of the target biomolecule by endogenous ligands. Binding assays are also routinely used in finding and defining interaction partners and interactions linked with diseases.

Binding assays rely on the quantitative/qualitative detection of binding partners as well as the resulting binding complexes. For this purpose, either the target biomolecule, ligands or both need to be labelled. Many labelling/detection techniques are used to perform binding assays including radioligand assays, affinity chromatography, surface plasmon resonance, isothermal titration calorimetry and light-based techniques using absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence readouts.1 Here we focus on binding assays based on light detection/labelling techniques commonly used in microplate readers.

Many binding assays using microplate readers for detection of a light-based readout have been described in the literature or are available as kits. Light detection modes in common use are: absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, FRET (Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer), Fluorescence polarization (FP), TRF (time-resolved fluorescence), TR-FRET (time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer), and AlphaScreen/AlphaLisa. A detailed description of how these approaches are used to determine binding affinity parameters is included in the blog How to determine binding affinity with a microplate reader.

In general, these detection techniques are used in affinity binding assays to determine KD, or in competitive binding assays for drug screening. However, they markedly differ in sensitivity, ease of setup and cost. In this blog, detection techniques are listed in the order of lower to higher relative sensitivity and examples provided to highlight the advantages and disadvantages of each. Sensitivity in a binding assay is often determined by calculating the limit of detection (LOD), defined as the minimum concentration of labelled ligand/complex that can be detected versus the blank. Although the LOD value is very specific to each individual assay, general relative trends can be ascribed to each technique mentioned below.

Absorbance is the measurement of the amount of light that passes through a sample at a particular wavelength. The absorbance measurement (A) is a ratio of the intensity of the light transmitted and the intensity of the incident light. As many compounds absorb light, impurities in the assay mixture can interfere with the compounds you are trying to detect in a binding assay, giving rise to a high background signal. Thus purified reagents or multiple washing steps are needed in absorbance-based binding assays. Despite these constraints, absorbance-based binding assays are low cost as no labelling is required for detection of a chromophore.

The most common absorbance-based binding assays are ELISA (Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay) assays. Absorbance ELISA binding assays utilise antibody pairs specific for the tested ligand and target biomolecule. While one antibody is used to bind the biomolecule or ligand to the microplate surface, the other antibody binds the second binding partner. The binding complex is detected by a colorimetric enzymatic reaction coupled to the second antibody. Any unbound binding partners in solution are removed by multiple washing steps. Traditional ELISA assays require significant time (3-5 h) due to washing steps, in part to ensure that the absorbance readout does not have high background noise. Increasingly, more absorbance-based ELISA kits are available that streamline the handling process by requiring only a single wash step during sample preparation.

Few compounds in nature fluoresce at visible wavelengths. Labelling the ligand or biomolecule in a binding assay with a fluorescent tag can significantly increase the sensitivity of an assay versus an absorbance-based method. In general, a better limit of detection and signal linearity over a much larger concentration range can be achieved. Furthermore, fluorescent labelling of small peptides and proteins can be easily achieved in most cases by using available, inexpensive reagents.

A serious drawback to the use of fluorescently labelled ligands in binding assays is the fluorescence quenching associated with receptors on cells or other large biomolecules. Fluorescence quenching can be due to a change in the conformation of the fluorescently labelled ligand, a change in its oligomeric state or the presence of nearby tryptophan, tyrosine, methionine, or histidine residues in the binding complex. This leads to a loss of the correlation of the intensity of the fluorescent signal with the concentration of the ligand or ligand/biomolecule complex. In turn, this leads to a loss of sensitivity and accuracy of the assay itself.

Although fluorescence-based binding assays are in general more sensitive than absorbance, they can still suffer from background noise. This is especially true where cell lysates are being analysed for detection of biomarkers. The many impurities within these samples can be problematic and purification steps still need to be performed. Light detection techniques have been developed to lower this non-specific signal, where the fluorescent signal does not directly come from detection of the fluorophore, but rather is moderated in some way to eliminate the background noise. Fluorescence polarization is one such technique.

Fluorescence polarization relies on the excitation of a fluorescent molecule with plane polarized light. When a fluorophore is excited with light there is a lag time (fluorescence lifetime) before it emits light of a longer wavelength. Small molecular weight molecules (<20,000 Da) labelled with fluorescein, can rotate in the assay buffer many times during their fluorescence lifetime. If polarized light is used to excite many of these molecules at once, as in an assay solution, then the light that is emitted is unpolarized, as the molecules are randomly orientated relative to each other when they emit. This effect can be used for binding assays when the small, labelled molecule is bound non-covalently to a much larger protein and the combined molecular weight is greater than 30,000 Da, the complex will not rotate very much at all during the fluorescence lifetime of the fluorophore (large molecules experience greater drag forces in solution). If a large molecular weight complex is excited with polarized light the light emitted will remain polarized (Fig. 1). This property has been used widely for binding assays in general. Only one of the binding partners needs to be labelled, which makes the assay relatively easy to setup and relatively cheap. Non-specific noise is significantly eliminated since only polarized light is detected. One drawback is the molecular weight limit on the labelled binding partner. This needs to be below 30,000 Da (for fluorescein) and preferably much lower, otherwise the labelled molecule will emit polarized light irrespective of whether it is bound or unbound to another protein.

This Application Note on a Competition assay using Fluorescence Polarisation to determine the Residence Times for Calcitonin and AMYR agonist, AM833, demonstrates, that fluorescence polarization can be employed to determine association and dissociation rates of ligand receptor interactions. In the AppNote “Studying the molecular basis of antibiotic resistance by assessing penicillin interaction with PBP5 using fluorescence polarization” a fluorescent penicillin derivative was used to monitor the interaction of penicillin with different variants of the penicillin-binding protein 5, which is responsible for the cross-linking of the bacterial cell wall.

Another technique to significantly eliminate background noise is Time-Resolved Fluorescence (TRF). The approach here is to use differences in fluorescence lifetime to separate the fluorescent signal of interest. Most fluorophores have a fluorescence lifetime of less than 10 ns. The lanthanides europium, terbium, dysprosium and samarium, however, have very long lifetimes, ranging from 1 µs to 1 ms. In a typical TRF binding assay, one of the binding partners is labelled with a lanthanide, the sample is excited at the lanthanide excitation maximum (347 nm), and a time delay is introduced before detecting the signal (typically 400 µs). The time delay allows any background signal from fluorescent impurities in the sample to decay, leaving only the lanthanide fluorescent signal for detection. This significantly improves the sensitivity over a simple fluorescence binding assay, with even less need for sample purification.

TRF has been used extensively in ELISA assays. The DELFIA TRF assay system developed by PerkinElmer (now Revvity) is one example and uses a europium label for detection. Many matched antibody pairs are commercially available that are specific to a biomarker of interest.

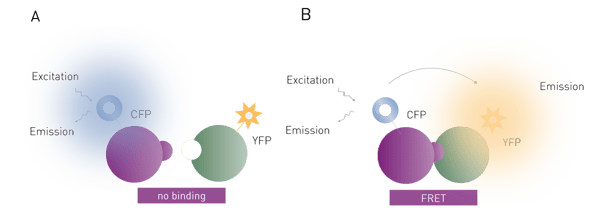

FRET is the radiation-less transfer of excitation energy from one fluorophore to another. Typically, the fluorophore that is directly excited by light is termed the donor and the fluorophore excited by FRET is called the acceptor. FRET can only occur between a pair of fluorophores when the distance between fluorophores is less than 10 nm. In addition, the emission spectrum of the donor must overlap with the excitation spectrum of the acceptor.

FRET is widely used and effective for binding assays (Fig. 2). The two binding partners (e.g. proteins, DNA) are each labelled with a fluorophore. If the two partners form a non-covalent interaction, then irradiation of the donor fluorophore will cause the acceptor to fluoresce as well via FRET. In some ways, FRET can be thought of as a fluorescent cascade (or domino effect) where one fluorophore excites the other, which subsequently releases fluorescent light without direct excitation. The FRET signal given off by the acceptor fluorophore is very specific to the binding interaction being studied. FRET assays therefore are much more sensitive than simple fluorescence assays, which significantly decreases the need for purification steps in an assay. Many assays are possible in the presence of cell lysates. The main disadvantage of this method over fluorescence polarization is the need to label both binding partners, which adds to the complexity and cost of setting up such a binding experiment. However, FRET-based binding assays are not limited by the molecular weight restrictions of fluorescence polarization.

The app note Using FRET-based Measurements of Protein Complexes to Determine Stoichiometry with the Job Plot shows how the assessment of protein-protein interaction stoichiometry has been successfully adapted to a microplate reader using a FRET-based approach.

The app note Using FRET-based Measurements of Protein Complexes to Determine Stoichiometry with the Job Plot shows how the assessment of protein-protein interaction stoichiometry has been successfully adapted to a microplate reader using a FRET-based approach.

TR-FRET binding assays can be thought of as modified FRET binding assays where the acceptor fluorophore is replaced with a lanthanide. They are often used for studying signalling pathways and for screening agonists/antagonists of G-protein coupled receptors. In this talk, Prof. Charlton gives an overview on how TR-FRET can be used to study and optimise binding kinetics.

The use of lanthanides allows both the introduction of a time delay before reading the assay and extra specificity in detection of the donor fluorophore via FRET. TR-FRET provides much greater sensitivity in a binding assay than either method alone due to decreased background fluorescence. This increased sensitivity allows a good LOD with much smaller volumes of reagents. A signal can be detected in volumes as small as 2 µl, with minimal purification of analytes required. This allows the use of 384-, 1536- and 3456-well microplates making TR-FRET a method of choice for high-throughput screening (HTS) binding assays. There are four major chemistries that when combined with appropriate antibodies (and other affinity tags such as biotin) allow detection of a huge number of binding interactions: Homogeneous Time Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF®), LanthaScreen™, Lance® and THUNDER. The donor and acceptor characteristics for the three are shown in Table 1. All these chemistries are available in kits for screening for specific biomarkers and various binding partners. Strategies are also available for labelling new and novel binding partners.

Table 1: Donor and acceptor characteristics of TR-FRET technologies.

| TR-FRET Chemistries | Donor | Ex Max | Acceptor | Lanthanide Em Max | FRET Em Max |

| Lance | Eu-Chelate | 347 nm | APC | 620 nm | 665 nm |

| HTRF | Eu, Tb Cryptate | 347 nm | XL665(APC), d2 | 620 nm, 490 nm | 665 nm |

| LanthaScreen | Tb-Chelate | 347 nm | Fluorescein | 490 nm | 520 nm |

| THUNDER | Eu-Chelate | 347 nm | Far-red dye | 620 nm | 665 nm |

In addition to commercially available kits, TR-FRET donor and acceptor pairs can also be combined freely as long as the donor emission spectrum shows sufficient overlap with the acceptor excitation spectrum as shown in AN 388: Differential binding of ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol derivatives to type 1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1).

All TR-FRET experiments have two emissions, one via FRET excitation of the fluorophore and one emission from the lanthanide. Most TR-FRET experiments calculate the FRET ratio (signal of fluorophore/signal of lanthanide) rather than just the FRET signal. Calculation of the FRET ratio (665 nm/620 nm, in this case) eliminates possible interference from the media and means the assay is unaffected by the usual experimental conditions (e.g. culture medium, serum, biotin, coloured compounds).

In the scientific talk Targeting the type 1 cholecystokinin receptor to screen for novel obesity treatments a TR-FRET binding assay was established to filter out orthosteric or negative-allosteric binders. There are also examples of TR-FRET competitive binding assays which read two signals at the same time (multiplexing). These assays typically use a terbium-labelled donor, and a green and a red dye as the acceptors.2

In his testimonial, Pioneering Pre-Clinical Drug Discovery with Advanced Assays, Nick Holliday from Excellerate Bioscience and the University of Nottingham discusses the benefits of the PHERAstar® FSX for TR-FRET-based kinetic binding analysis.

Bioluminescence has been used extensively in biological research for some 40 years. Luminescence assays use luciferase enzymes to generate light. The first luciferase to be cloned in bacteria was the firefly luciferase from the North American firefly.3 Over the years, many luciferases have been identified. Luciferases react with their natural substrates (luciferin for the American firefly) and in the presence of ATP and oxygen produce an oxidation product (oxyluciferin for the American firefly). The product is formed in an excited state. Light is produced when the excited electron relaxes to a lower energy level.

In the past 20 years, luciferases have increasingly been used for BRET binding assays. BRET assays are very similar to FRET and TR-FRET assays, except that the donor used for one of the binding partners is a luciferase. The incorporation of a luciferase as the acceptor allows direct expression of a protein of interest (such as a GPCR) with the luciferase label and this can be used in cell-based binding assays relatively easily as compared to FRET and TR-FRET experiments. The other important advantage of BRET assays is that no external light is needed. The only requirement is addition of a luciferase substrate. This alleviates complications such as fluorophore bleaching and unwanted generation of background fluorescent signals from other cellular components, when using a light source to excite your fluorophore or lanthanide. The first BRET assay was reported in 1999. 4 Since then many luciferases have been tried as donors as well as many fluorophores as acceptors. The most important advance was the engineering of the NanoLuc luciferase, a small molecular weight enzyme that has a luminescence output 150x greater than Firefly. The NanoLuc luciferase has been developed into a BRET platform called NanoBRET™ by Promega, for the study of protein-protein interactions in live cells.

One important application of BRET is the study of the binding of agonists to their receptors on the membranes of cells in real time. This is also further discussed in the webinar: “Real-time profiling of receptor pharmacology”.

Another application example can be found in the application note “Identification of peptide ligands for orphan GPCRs by measuring Ca2+ -induced luminescence in transfected cells”, using the magnetic stirrer and heater as well as injecting living cells into the assay system.

Recently, CRISPR technology has been used for gene editing the DNA of live cells to label a GPCR of interest with NanoLuc. The resulting fusion protein acts as a BRET donor and over-comes the need for exogenous donor expression (an example is provided in this application note). This approach greatly extends the usefulness of BRET in the study of protein-protein interactions in live cells.5 Alternatively, such BRET-based test systems can also be utilized to study G-protein dissociation. In the past, BRET assays have suffered from low sensitivity and dynamic range as compared to TR-FRET and AlphaScreen. This has been largely due to low signal intensity, largely because of the luciferases used. However, the development of NanoLuc has changed this and the use of BRET for binding assays and high throughput screening continues to grow. Another way to study interaction using luminescence is by HiBiT CETSA. This assay utilises a fragmented HiBiT nanoluciferase fused to a target protein of interest (POI). Under physiological conditions, this fragmented luciferase can be completed to form a functional enzyme while heating up the protein will prevent this due to protein denaturation. The HiBiT CETSA is used for protein binding by adding potential ligands to this reaction. Here, binding of a ligand to the POI will result in a measurable increase of its thermal stability. Alternatively, fragmented nanoluciferase can also be used as a direct measure of protein binding as highlighted in the application note: Identification of androgen-disruptors using a cell-based androgen receptor dimerization assay, which is based on an NanoBiT® assay.

The AlphaScreen® (amplified luminescent proximity homogeneous assay) light stimulation platform for binding assays has been available commercially for around 20 years. The heart of these assays consists of two distinct types of polymer beads. The donor bead contains a photosensitiser, which when irradiated with 680 nm light generates singlet oxygen in the surrounding aqueous media. The acceptor bead incorporates a chemiluminescent compound. Singlet oxygen has a lifetime of ~4 µs and travels about 200 nm in solution during this time. If the donor bead is in close-proximity to the acceptor bead, then the acceptor will produce light via luminescence at wavelengths of 520-620nm. The beads can be used to label various proteins of interest, via antibodies (specific to the targets) that are attached directly to the beads. Fluorescence always proceeds by emission of light at a longer wavelength than the wavelength at which the fluorophore is excited. AlphaScreen works in the reverse direction. Therefore any background fluorescent signal from the 680nm stimulation is not detected using this method. This generally makes the technology very sensitive.

A typical example of a ligand binding assay employing AlphaScreen technology is the development of a competitive binding assay for studying the interaction of the protein ENL-Yeats domain binding to Histone H3. The ENL-Yeats protein complex binds via the Yeats peptide to Histone H3 when several lysine residues on the histone are either acetylated or crotonylated at the lysine side chain amino group. The histone interaction with Yeats-ENL has been shown to be a major driver leading to several types of acute leukaemia.

One problem with the AlphaScreen technology is that AlphaScreen beads are light sensitive and need to be prepared in low light conditions. The signal decays slowly over time and microplates need to be read very soon after they are prepared. The signal does not last if plates are stored in a refrigerator overnight, in contrast to TR-FRET based mixtures which last much longer when prepared in a microplate. Although background fluorescence is removed, antioxidants and metal ions that can react with singlet oxygen can strongly affect the signal. To counteract these drawbacks AlphaLisa binding assays were developed, which employ acceptor beads that are infused with europium resulting in greater sensitivity and reliability.

As this blog shows, there are many ways to perform binding assays. Which one to choose will be determined in part by the plate reader that is available, the cost of various kits or the cost of labelling the binding partners for a particular assay.

Plate readers come in various configurations from low budget models to high-end units capable of reading any of the assays described here with high sensitivity. However, most models, apart from dedicated absorbance-only microplate readers can read as a minimum fluorescence, luminescence, and absorbance. If this is the case, then fluorescence-based binding assays would be preferred over absorbance-based ones as they give a more intense and specific signal over a much wider range. In the case of ELISA assays less wash steps are involved in a fluorescence-based assay. In fact, nearly all absorbance assay kits on the market today have a fluorescence-based equivalent including enzyme assays, protein concentration assays, cell viability assays and more. The fluorescence-based kits are slightly more expensive but are simpler and more sensitive to use. High-end readers, compatible with further detection techniques, offer an even greater choice of kits for performing binding assays, including FRET, TR-FRET or AlphaLisa-based assays. These combine the advantages of an easy setup with greater sensitivity.

A further consideration is that no one technique is perfect. The light signal from each technique can be affected in an unpredictable manner by the presence of individual compounds in a library, in cells or bodily fluids. In high-throughput screening of compound libraries, it is common practice to develop an assay based on a few techniques, as actives identified in one assay do not totally overlap with those identified in another. To give an example, in one study, two TR-FRET (Lance, HTRF) and one AlphaScreen assay were developed to screen 90,000 compounds, for inhibitors of SIRPα-CD47 binding. In a pilot screen, the three assay technologies displayed varying activity rates (0.2% for Lance and 1.1% for HTRF and AlphaScreen) with some overlap. The authors found that the Lance assay gave less false positives than HTRF and used Lance for the primary screen and AlphaScreen as an orthogonal confirmation assay.6 It is thus crucial to test various methods and determine the best suited for performing binding assays for your target of interest.

In conclusion, for the many binding assays found in the literature, most can be categorised according to the light detection technology being used. Likewise, most of the light detection techniques can be used to develop a binding assay and it is crucial to select a suitable microplate reader. The CLARIOstar® Plus and the PHERAstar® FSX are BMG LABTECH´s go-to readers for performing binding assays and are compatible with all common detection technologies. While the CLARIOstar Plus offers maximal flexibility in binding assay performance due to the Linear Variable Filter monochromator and EDR technologies, the PHERAstar FSX combines highest sensitivity and speed due to the SDE feature and a laser-based light source.

Moreover, the AAS system provides a steady temperature that is unaffected by external environmental changes while the plate reader is operating. This provides improved assay stability for temperature-sensitive reactions such as binding reactions.

Absorbance plate reader with cuvette port

Powerful and most sensitive HTS plate reader

Most flexible Plate Reader for Assay Development

Upgradeable single and multi-mode microplate reader series

Flexible microplate reader with simplified workflows

Degrons are specific sequences of amino acids or structural motifs within a protein that are important for targeted protein degradation. Find out how microplate readers can advance research into natural and engineered degrons.

Gene reporter assays are sensitive and specific tools to study the regulation of gene expression. Learn about the different options available, their uses, and the benefits of running these types of assays on microplate readers.

Innovation for targeted protein degradation and next-generation degraders is gathering pace. This blog introduces some of the different approaches that act via the lysosome or proteasome.

The choice of assay for targeted protein degradation studies is crucial. But what is the preferred assay and detection technology for your specific research needs and microplate reader?

Molecular glues are small molecules that help target unwanted proteins for destruction by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Find out how microplate readers can advance molecular glue research.

Cannabinoids offer exciting opportunities to target diverse diseases with unmet needs. Learn how microplate readers can help improve our understanding of drug screening and drug signaling events to help advance cannabinoid research.